- Home

- Rachael King

Magpie Hall Page 2

Magpie Hall Read online

Page 2

The magpie came home with me at the end of the holidays. My mother tried to make me keep it in the shed, but I would not let it go. It perched in my room and kept a guard over my dreams as I slept. I took it to school for show and tell and all the children wanted to touch it at lunchtime. They sidled up, measuring me, not sure whether to revile or worship me. It was a dilemma they would face all through my school days.

Now, the menagerie room looked as though Grandpa had just stepped out for a cup of tea. The big work table, hip height, dominated the centre of the room, and the tall stools I used to balance on were dotted around it. His instruments were lined up ready to use: scalpels, brushes, brainspoons. Containers of eyes, descending in order from biggest, like marbles, to the tiniest of rodents’ beads. Glass cases cluttered with jars and small animals stood with their backs to the walls.

I took a moment for it sink in: this collection was now mine. I owned it. Every parrot and hummingbird, every tui and snarling stoat.

Outside, the day was dulling. A small whirlwind picked up a pile of leaves and scattered them across the vast lawn.

I didn’t know how long it had been since Grandpa was well enough to work in this room. My parents tried to get him to move in with them, especially in those last few months, when he was really ill, but he refused to move. He said he was damned if he was going to live out his last few months in a house in the city where he couldn’t see the stars at night. But we all had busy lives and nobody could afford to take the time off to care for him indefinitely at Magpie Hall.

He had grown up in this house, as had his father; his wife had died there; he had raised his children, seen grandchildren come and go. The house was far too big for one old man and his housekeeper, with no other dwellings for half a mile — and those the workers’ cottages up the hill, where Joshua the station manager lived with his wife and young children. Magpie Hall wasn’t built for this solitary life. Standing there, I felt its spaces echo around me, and realised it was the first time I had ever been there alone. And in that moment I understood why Grandpa had left the house to Charlie, in the sweet hope that it would be restored to a new generation, that the cycle that had passed with Grandpa would begin again, that Charlie might start a family there. And although Grandpa wanted to stay there until he died, I know that the silence got to him, that the house had lost some of its life since I had stopped coming as a child all those years ago. Its spaces were thick with regret. Its edges had faded and frayed.

Finally the family employed a nurse to look after Grandpa but we visited him often and in the end he said he preferred to have a near-stranger looking after him. When he couldn’t wash himself properly or go to the toilet unassisted, he would rather his family didn’t have to do it for him. It was about dignity, he said.

I moved back to my home town after my grandmother died, to take up my university studies and to be closer to Grandpa. I grew up in the right part of town, went to all the right schools. By day it was a pretty, safe place, covered with bright flowers or a sprinkling of frost, depending on the season. Old money lived there, apparent in the huge colonial houses that sat behind brick walls and hedgerows, shutting out the world. By night it became a city where prostitutes were found floating in the river; where teenage girls were raped or murdered; where a young man could be beaten to a meaty pulp for wearing pink sneakers; where tourists were knifed in the town square for talking funny; where the citizens were held captive by boy racers, who circled the perimeter like sharks, engines growling and tyres smoking. The good folk cowered in their houses and waited for the sun to rise. I had left as soon as I was old enough, swearing never to return, so when I did, I chose to live as far away from the town centre as possible, over the hills in the industrial port.

With the bare bulb now illuminated, the animals threw sharp shadows on the walls. Exotic butterflies and beetles were trapped behind glass, and the light reflected off their wings and bodies. Grandpa had told me about them — they were from Henry’s vast collection, captured in Africa and Australia and Brazil. The most marvellous part of the story was that he hadn’t just acquired them; he had caught them himself. Who knew how much had gone into each specimen, how much it had cost him, in money, danger and sweat? And here they were, colours as alive as ever.

I let my gaze slip to the glass cases. These had been my guilty pleasure as a child. The kids at school didn’t believe me when I told them what they contained: not only stuffed animals but jars of creatures preserved in what I supposed was formaldehyde or alcohol, with faded labels written in old-fashioned ink: a coiled thin white snake, with a label that read Zamenis hippocrepis, Egypt, 1882; Squid, Aegean, 1875 stuffed into the jar, its tentacles wrapped around themselves and pressed against the glass. More jars were stashed behind them, three deep. One snake, Dipsas dendrophila, from Sumatra, had large scales on its black and white body, giving it the appearance of a fish floating in water. I don’t think Grandpa even realised how much time I spent in this room when he was out on the farm. I knew where he kept the key to the case and I hid in the menagerie room with Henry’s collection while the family forgot my existence. I opened the doors, moved aside the jars at the front and reached in to pull one from the back: one of the good ones that only I knew about. I would never have shown my little brother what I now held in my hands, suspended in the heavy liquid, turning in the light: a human foetus. Next to the foetus on the shelf, a pair of tiny feet. A baby’s feet, soles pressed against the glass, with rosy rings lacing its toes. The label read: Smallpox, 1885.

I tried not to think of the story they suggested — the parents’ grief, and whether they had knowingly donated their child’s extremities to science. Whether they also kept something of it, a grisly memento mori. Perhaps it is bad enough to lose a child, without having to be reminded of it all the time.

What brought me back to look at the jars again and again was the fact that these creatures, human and animal, had lived more than a hundred years before and yet here they were in my hands. The person who had preserved these had the power to bestow immortality.

I pulled out the letter the lawyer had given me at the reading of Grandpa’s will. I had read it only once then put it away, too distraught by the death and immersed in my problems. But the letter was one of the main reasons I was here, so I sat on one of the high stools and read it again.

My dear Rosemary,

I am dictating this to Susan, my nurse, as my handwriting is slow and shaky these days. By the time you get this you will know that I have left you my taxidermy collection and the other contents of the menagerie room. The rest of the family might think it strange that I am leaving it all to you, but as you are the only one who has ever taken an interest in taxidermy, it is absolutely fitting that you should have this collection. Much of it, as you know, belonged to my grandfather, Henry Summers. He taught me the art, as I taught it to you. I know you don’t do it so much any more, but I hope that this collection will inspire you.

You will find some rather unpleasant items in this collection, my dear. I never showed them to you because I didn’t think you were old enough to understand, and by the time you became an adult, well, you’d stopped asking. To understand why they’re here, and why I have kept them for so long, you need to know a bit about your great-great-grandfather.

You know that he came here in the 1880s and that he restored this house. He was from a very well-respected family in England, a gentleman with prospects and many illustrious friends, including, I understand, Edward VII himself. He was not a warm person, my grandfather, at least not to me, which is one of the reasons I tried to be more to you. He taught me things, but I never felt it was out of love for me. So, no, he was not warm, but he was a fascinating man, and for that I was proud to be his grandson. You know that he was a collector, and that he visited all manner of countries in pursuit of the strange and the wonderful. He wasn’t content, like many men of his social standing, to spend money amassing his collection of curiosities, just by waiting for consignm

ents to arrive from the far reaches of the earth. He went to get them himself. That is what brought him to New Zealand — the search for the moa and the huia, and perhaps slightly less nobly, the search for Maori artefacts. What he didn’t count on was meeting a woman, falling in love and marrying, thereby sealing his fate, and all of ours, to be born New Zealanders.

The woman he loved was not my grandmother, who was his second wife. The first drowned in the river. Her body was never found. I believe that he cared for my grandmother, but I don’t think there was a great deal of love between them. In fact I think she was scared of him, as we all were. He had a terrible temper and would fly into such rages that we all had to stay out of his way. Towards the end of his life, they got much worse, for no reason, and if it’s possible for someone to die of anger, I would say that this is what killed him in the end. He would lock himself away in the room that housed his special collection, his cabinet of curiosities he called it, and nobody was ever allowed to see it. I sometimes listened at the door and heard him talking to himself, and I heard him crying once, and saying the name ‘Dora, Dora,’ over and over again. Dora was his first wife.

I never understood why he just stopped building up his collection. After Dora passed away, he never left the country again, but threw himself into developing the farm, which was passed on to my father and eventually to me.

He left the cabinet to the British Museum. After he died, my father found it all boxed up, ready for shipping, with instructions that it was not to be opened until it arrived at the museum. Unfortunately it seems that it got lost in transit, and we never found out what happened to it.

What I’m trying to tell you, my dear, is that you now own not just my animals, but the collection of a great explorer and a great man. Unfortunately you do not have the cream of his collection, whatever was in it, but if it were ever found again, it would be yours, too. Or perhaps it would belong to the British Museum, I’m not sure. So spare a thought for Henry Summers when you look at his more gruesome artefacts. I trust that you will know what to do with it all.

One more thing, which I never told anyone, but I know now, after talking to your father, that you will be interested: when I was a boy, I came upon my grandfather bathing in the Magpie Pool. He dressed himself quickly when he saw me, but not before I saw that his chest and arms were covered with tattoos. I was terribly shocked, because tattoos in those days were for sailors, and circus freaks. Not for gentlemen. Perhaps it is different nowadays, as your father has told me you now have one or two decorations of your own. It is the natural order of things for the old not to understand the young, so I will leave it at that.

I can’t tell you what it means to me to be able to leave all of this in your hands. You gave great joy to this old man in those hours we spent together at the workbench. I’m sorry things didn’t turn out more happily for us.

Live a good life, my darling granddaughter. And may this collection bring you as much joy as it has me.

Your old Grandpa

I felt as though he were standing in the room with me, breathing my air.

Someone once said that you don’t ever get over grief; you just learn to live with it. Sometimes when I was alone, the crying would be triggered suddenly and, just as quickly, it would be gone and I would feel unblocked, like a drain.

Gradually the tears stopped and I was able to wipe my face on my sleeve and look at the letter again. I wished it had been longer, that Grandpa had sat down earlier and written more about Henry. Now that it was threatened, I felt a sudden hunger to know more about the house, about the man who had built it and the woman for whom it was intended.

But I took four very important facts from that letter. The first was that Henry had lost his wife and her body was never found, which was the cause of the rumours that he had done away with her. I don’t know why, but I imagined theirs was a great love, the kind of love you only read about, and that I certainly have never experienced. I had found only failure, again and again.

The second fact was that he had a temper on him. Third, that he had a cabinet of curiosities which nobody ever saw. And fourth, that he was inked. And that was the fact that sealed my connection with this man, my ancestor, Henry Summers.

I got my first tattoo at the age of seventeen: Tess, etched in cursive script into the spongy flesh of my inner forearm. Above it, a horseshoe; below it, memento mori — remember you must die. My poor skinny mother, clad in cashmere and gold, never forgave me for that first tattoo. She called it morbid, and insisted I cover it whenever I was near her, but I knew it for what it was: a reminder that because everything must die, we must make the most of the life we have. She didn’t like any of my subsequent tattoos, of course, but it was that first one that disturbed her the most. She just wanted to forget.

It was bad enough, she said, to come upon the dead animals I collected and stored in the freezer at home: a bellbird I’d found floating in the swimming pool; any number of sparrows and mice the cat had brought me. I practised on their bodies to hone my taxidermy skills. She said that death clung to me and she sometimes couldn’t bear to look at me.

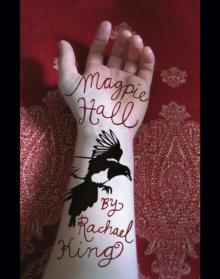

I got my latest tattoo — my tenth — just before coming here. It was a single magpie, wings outstretched. Roland had bent his long body over my wrist, pulling the skin taut with a rubber-encased thumb and forefinger, while I felt the buzz and sting of the needle over gristle and tendon, and smelt the sharp tang of my own sweat, mixed with the pervasive smell of methylated spirits. If there is one thing that tattooing and taxidermy have in common, it is that smell. Tattooists use meths to sterilise the instruments. Taxidermists use it to dry the last stubborn bits of flesh so they peel cleanly from the bone. Perhaps that smell, so much a part of my childhood, is what keeps me returning again and again to the tattoo parlours.

From Grandpa’s letter, it was obvious he didn’t know something that I had only recently found out: that tattooing was hugely fashionable among the British aristocracy in the late nineteenth century. Men and women flocked to the tattoo parlours of London, where they lay in comfort to have their skin inked. The Prince of Wales was tattooed in Israel, then again in Japan; he urged his sons to visit the same Japanese tattooist and they obliged.

People often ask me if my tattoos hurt. I have only one answer for them. Of course they fucking hurt. But it’s for such a short time, and the results are forever, so the ratio of pleasure to pain is great. You hear people talking about how sweet the pain is, how after a while it becomes a tickle, how it gives them a rush. I just feel the pain and do it anyway. The worst is when it’s close to bone, like the bluebirds on my chest, or where nerve-endings collect like blossoms beneath the skin. Unsuspecting girls get tattoos on their buttocks, but the pain there is enough to make them vomit. One girl I know passed out when she had her shaved skull inked. After that she grew her hair long and never saw it again anyway.

Roland did most of my work, and he let me rent the flat above his shop for next to nothing. He told me stories about gaggles of bare-midriffed girls who stood at the shop window for half an hour giggling and arguing over flashes before choosing one. They all had the design — something abstract, tribal — engraved on their lower backs one after the other, as though on a factory conveyor belt. A tramp stamp, Roland called it. He didn’t like doing spontaneous work, thought such people were most likely to regret their decision and want to get their tattoos removed later in life. He did his share of celtic armbands in the nineties grunge boom but preferred it when people brought him original designs he could adapt, or they gave him an idea of what they wanted and they worked on it together, on paper, for a few weeks, before settling on the ideal image.

I like my tattoos vibrant, with strong block colours, nothing Gothic or heavy metal about them. I either favour Roland’s one-offs or old-fashioned flashes such as sailors wore in the early part of the twentieth century: hearts and shamrocks and ribbons. I love the sense of history that comes with those kinds of tattoos, when the only women to wear them were tattooed la

dies in a circus. Some of my designs are overtly feminine — flying teacups and bright flowers.

Roland reckoned that his shop had been a tattoo parlour when it was first built in the 1880s. It was right by the port, and every morning I awoke to the groaning machinery of the giant cranes that crouched like praying mantises on the wharf, offloading cargo from ships, or depositing coal and logs that had come by train from the West Coast overnight. In the nineteenth century there would have been no cranes, but the port would have heaved with activity nonetheless, sailors descending on the town’s pubs and brothels, looking for a quick flurry of transgression to liven their otherwise monotonous lives. When Roland had stripped off the wallpaper of what was a hardware store when he moved in, he’d found a layer covered with the hand-drawn flashes popular back then, such as ships and anchors, sea monsters and English roses. He kept them behind plastic in a scrapbook and showed them to me once. They were faded and the paper they were drawn on was dark and greasy, but you could make them out all right. I longed to touch them, to smell the paper, which I imagined was impregnated with lantern oil and pipe smoke. But Roland stood over me as I looked and took them off me when I was done, protective. He showed me the signature at the bottom of one. It looked like a squiggle to me, but he insisted it said ‘McDonald’.

After the black outline of the magpie, he had started on the shading, and the blood had begun to run. He wiped it away with a cloth as he worked. He finished with white ink. It looked bright, even against my pale, almost blue wrist. The lines were raised and rimmed with red, but they would go down in a few days and I was to rub it with cream twice a day to stop scabs from forming.

Magpie Hall

Magpie Hall