- Home

- Rachael King

Magpie Hall Page 3

Magpie Hall Read online

Page 3

‘I do know the ritual,’ I reminded him as he wrapped it in clingfilm.

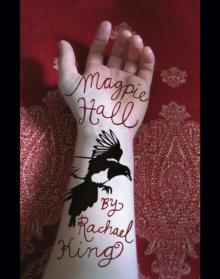

‘I still have to tell you,’ he said. ‘One day you might forget and you’ll come back complaining when the scabs fall off and the whole thing is ruined.’ He grabbed my elbow and pulled my wrist towards his face. ‘It’s a good one,’ he said. ‘Why a magpie?’

‘One for sorrow,’ I said, and paid him.

It took me three trips to carry my groceries to the kitchen and all of my things upstairs. My wrist ached, but the magpie was unharmed. I chose the red room to sleep in, leaving the other five alone. It wasn’t the biggest — that was my grandparents’ bedroom, with its two sagging single beds — but it was the warmest, with its own fireplace and a northern aspect to catch the winter sun.

I unpacked my laptop and printer and the stacks of files, and put everything on an oak table away from the window. Looking at the novels I was supposed to be analysing, I reassured myself I had done the right thing. Jane Eyre never settled for being Rochester’s mistress, just as she wouldn’t settle for marrying St John Rivers. She would have lived happily alone if it weren’t for the convenient fire that did away with Bertha. I couldn’t see that happening to Hugh’s wife, and I wouldn’t have wished it upon her even if I could.

I hung a few clothes in the wardrobe — a couple of dresses and a heavy coat that I had picked up from the St Vincent de Paul store by the university. When I closed the wardrobe door I caught sight of myself in the full-length mirror: sunken eyes and pale face, the skin of my lips puckered from dehydration. Not a pretty sight. At least I didn’t have mascara running down my cheeks from crying — since I’d made the decision to come here I hadn’t bothered with the most basic of grooming. The fringe on my straight brunette bob stuck out instead of being blow-dried flat. Dressed entirely in black, I looked as though I had come from a funeral. I pinched my cheeks to tease some blood to the surface, and blew into my cupped hand, checking my unbrushed breath. Not too bad, considering.

The familiar cold of the house was closing in on me. I turned on the ancient panel wall heater with its fake wooden veneer and it ticked and groaned into action. Then I lay down on the bed, pulled the musty eiderdown over me and waited for the day to finish.

He is a collector of wonders, of dreams and sometimes nightmares. Of the lesser sulphur-crested cockatoo and the katydid, of turret shells, brittlestars and the Morpho menelaus. His collection is full of the treasures he has gathered in his travels. Tribal weapons and fantastic jewels, iridescent snakes, bodies bundled into jars. Animal, vegetable, mineral. He even has a mermaid: dessicated, mummified, the size of his torso. He is not stupid; he knows it is a fake, assembled by some trickster from the remains of a monkey and a fish, but it is enough of a sight to find its way into his wondrous cabinet of curiosities. His Wunderkammer.

He has been collecting nearly his whole life. He has long since forgotten to start a career, anything that his father might deem useful, but what is the point, he thinks, when he is contributing so much to the world’s understanding of itself, when his travels bring him both pleasure and knowledge, a sense both of importance and of utter insignificance in the universe?

His cabinet has grown and changed shape, and has spilled over onto his body. He is now the collector of real, womanly mermaids, of dragons and fairies — things never seen before. He is a collector of ink, stitched into his skin.

The first tattoo he acquired in Japan, with the encouragement of his friend and travelling companion, George Norton, who wanted to see first hand the work of the man who had tattooed the Prince of Wales and, more recently, the Prince’s sons. Henry carries the memory of the day around inside him, still sharp: the cool of the silk cushions on his back as he stretches himself on the oor, naked from the waist up. Lanterns create a soft glow; he is wrapped in the warm caramel light. Hori Chyo, the master of the craft, grips his arm, stretching the skin as he works. The pain calms him. The explosion of anger he felt — sudden, white-hot, nearly spilling over before he could control himself — when George pushed in front of him and laughed in his face has been dulled by the prick of the needles. Prick, prick, prick, steady, like the beat of a metronome, Chyo swapping his needles as the thickness of the line and the colour dictates. The needles themselves are worthy of collection — intricately carved ivory — and when Chyo turns his back as he finishes, Henry slips one into his pocket, where he will later forget about it and prick his thumb, drawing blood, making the memory fresh. Afterwards, he will flex his arm and the dragon will move. He will stare at it, flexing and flexing while the dragon sways.

As soon as he disembarks in New Zealand, he sets off to find the port’s tattooer. He hesitates outside the studio, checking the address again on the slip of paper. He calls it a studio because this is what they are called in London, but this place is more like a dingy shop. Inside he can barely see in the gloom. A great shape moves and sighs in the corner, like a sea elephant turning on a rock. The air is thick with tobacco smoke and an ember glows in the darkness, flaring suddenly to reveal the shape’s face briefly before it sinks back into darkness.

Hello?

The leviathan lumbers to its feet, nods and picks up a lamp. The man holds the light out into the dark space between them. The look on his face is one of surprise, then acceptance — a shrug of the shoulders.

Yes? He spits on the ground.

Sir, I am told this is the place to get a tattoo.

For who?

Well, for me.

The man lurches forward and Henry takes an alarmed step back. The fellow has enormous greying mutton chops, a round belly and a swollen bottom lip, as though he has been in a fight.

Pay by the hour. I’ll do one of my own designs — he gestures around the room — or you can give me one of yours and I’ll make the best of it. His voice is monotonous, as though he has been standing on a street corner, selling his wares, like oranges, all day.

Henry decides to examine the man’s designs. The tattooer lights another lantern and now Henry can see that the mildewed walls are alive with pinned up pages, crinkled with damp. Some of the sketches are basic, just a few lines; others are breathtaking in their intricacy. Maritime images abound — anchors and ships, fish, dolphins and sea monsters. Sailors are obviously the main clientele in this port, where ships arrive daily, depositing their cargo and their inhabitants onto the shore. There are other depictions: flowers, and the faces of beautiful women, who stare out at him. Sweethearts long ago left at home, whether to wait or to marry someone else, who can tell?

He sees butterflies — green ones, yellow ones, papilios and brimstones, though he doubts the wearers care about their names; he sees biblical scenes, Christ’s crucifixion and his last supper.

The man is an artist. Any fool can see it. He deserves to be in a London studio, surrounded not by darkness and the smell of sweat and stale tobacco, but by potted palm trees and Persian rugs, electric lights, silk cushions, chaises longues. He could secure the patronage of any number of gentlemen, yes, even of noblemen and ladies. Why, the month he left he saw a tattoo on Lady Wentworth’s wrist; she hadn’t hidden it, had lifted her bracelet for all to see, a little bluebird of happiness, flying on her skin. This tattooer would do a better job of it — if his work on the skin is as accomplished as his sketches. Henry knows what a skill it is to transfer the art to the body.

What’s your name, man? asks Henry.

McDonald, the tattooer says.

You’re an artist, do you know that? Not just a tattooer.

The man grunts, laughs, spits. A tattooist, see. Artist, tattooer. Tattooist.

Yes, says Henry. Shall we begin?

He slips the card with the rose from his pocket. It doesn’t matter how widely he travels; England will always be his home.

The man is slow, but meticulous. He wipes away the red ink as it overflows. Each prick builds on the last until Henry’s chest sings.

We don’t get many like you, says McDonald. He smokes as he work

s. His instrument looks ungainly, pieces of metal tied together to deliver the ink under the skin, but he wields it like the finest of fountain pens.

Like me?

Gentlemen. That is, we have had one or two, always from London. Never the first time. They’ve always been bitten by the dragon.

Dragon? I haven’t heard that expression.

He chuckles. That’s because it’s me own. They’ve had one tattoo, maybe as a trophy, following the fashion, see. They know about the prince and the dragon what he got in Japan. They all want one like that to start with. Only then they want another. Like a fever. They don’t usually come back once they’ve settled in New Zealand though. Not the height of fashion around here. The local gentry would be shocked.

Thank you for the warning. I’m not much interested in fashion these days.

Then why do you do it? McDonald pauses in his work, leaves his wrist balanced, pressing against Henry’s sternum.

Why do you? Henry shoots back.

The man chuckles again. It’s in me blood. Me father was a sailor and he brought back tattoos from the romantic South Pacific. The most beautiful things I ever saw, the tattoos I mean. I knew I wanted to learn how to do it. To have it done. And to come here.

He spits on the ground. Not quite what I expected, he says, but I guess it’s home now. Now it’s your turn.

I do it to remember, says Henry.

Later, he puts his hand on his chest, feels the weight of it there on his rose, above his heart. He leaves it there while he stares out the window onto the manicured lawn and garden of a Mr Collins, who has offered to introduce him to local society. He feels cheated. He was led to believe that this country was a wild, untamed place, with strange wildlife and intriguing natives, but this city is nothing but a replica of an English town. He loves England, and wants to return some day, but he did not travel to the other side of the world to live the life of village fetes and smart shops, groomed grass and flowers. There is no adventure in these things.

He dampens down the flash of anger he feels rising in his chest by placing his other hand on the window, concentrating on its dents and undulations. The hand is knotted with scars. He snatches it away, leaving a starfish print in the mist caused by his own breath. Through it he sees the startling green of the garden after rain, pocked and warped through the glass. That other day, two months ago, when he put his fist through the window, the view had been of manicured lawns and stiff topiary; now it seems little has changed.

He had been attending a party that his father was giving for his sister. He’d had too much wine; the anger had taken hold unexpectedly, as it always does. He feels it physically, running through his body, flickering at the edges of his vision. It is always his body that responds, lashes out, with a fist or a foot, sometimes just his tongue, spewing out words he didn’t realise he was capable of.

He hadn’t minded the pain — it was nothing he hadn’t endured before. His knuckles, roughly stitched, made a pattern he found curiously beautiful; the skin bloomed purple and yellow around the cuts as they healed.

He had found the gaze of Miss Pringle as he stood grasping his wrist with blood trickling into his sleeve, and she had looked away, blushing and furious. His anger had seeped out of him, along with the blood. He could hardly remember what it was that had set him off, but he knew he had lost Miss Pringle for good, and he cared little.

His father called him into his study the next day, holding out a cheque, unable to look at him.

I have decided to fund your next expedition, he said. To New Zealand. You’ll continue to get your remittance, as long as you stay there.

He had said no more, but Henry heard the threat in his words. That he would be tolerated no longer. That if he was to have an income, England would no longer be his home.

This then, is all he knows of New Zealand so far. The backward seasons (frost in August!), the murky port, the tattooist, then the short train ride through the tunnel to a town modelled on England, with weeping willows lining the meandering stream (they call it a river but it is a trickle, really) and brand-new wooden buildings among the traditional stone and brick, and oak trees and delightfully proper society, with tea and dancing and church services. Flowers that bloom like manic grins in the gardens of streets named after English counties.

And now, a starfish print on a window and a party in his honour. He must be civil. He will meet important people here, for Mr Collins has invited the director of the museum, who will put him in touch with other collectors and taxidermists. With luck, the director will offer to buy some of his specimens — those he has brought with him and those he will acquire on his travels around the country, through the rugged land that he has yet to see for himself, to believe it even exists.

He moves away from the window as the other guests begin to arrive, announced by a servant. They seem hungry to meet him, to hear news of Home; the ladies in particular strike him as slightly vulgar in their need to know whether they’re as fashionable as their London counterparts. He doesn’t have the heart to be truthful, so they move away, beaming, after they have extracted their compliments.

He decides to make the best of it and begins to relax after his second brandy is safely in his stomach. He is even starting to enjoy himself when Mr Collins approaches him with a young lady on his arm.

May I introduce my daughter, Dora, says his host.

Miss Collins. Delighted. Henry takes her hand briefly. She wears long gloves — they reach almost to her armpits — and they are cool under his fingers. She is not like the other women, this one. She doesn’t bray, or giggle, and he feels her gaze penetrating his chest, where it flickers from his face, as if she knows of the recent tattoo there. Her eyes are dark grey, and her blonde curls look as though they have been subdued rather than coiffed.

And how do you find our little town, Mr Summers? I’m afraid you’ll think us rather dull after London society.

Have you been to London? he asks.

Yes. She looks at her father, who finishes for her.

I took Dora there last year, when I met your father. The journey to and fro lasted nearly as long as our entire stay there. It was quite exhausting. Dora loved it, but I confess in my old age I like New Zealand more and more.

Henry surmises that he can’t be older than forty-five. Well, he says to Miss Collins, I’m sure you fitted neatly into the society there.

You needn’t compliment me, Mr Summers. I have no illusions about being anything other than a simple girl from the colonies.

She glances sideways at her father, who has turned away to talk to someone who has appeared at his elbow. She smiles as though she has got away with some transgression, leans closer and lowers her voice. Forgive me, she says, but you have something just here. She touches her own lip, while her gaze drops to the floor, as if she can’t bear to look at his face while he finds the morsel of food.

Thank you, he says. People are so polite about these things. I might have walked about with it for hours.

She blushes. He chastises himself for suggesting she is improper, when he only wants to compliment her. Yes, he realises, of all the women here, she is the one he genuinely wants to compliment. But when he goes to apologise, she stops him with a shake of the fingers, as though they are wet and she is flicking water at him. Baptising him.

After Collins has steered her away, he is introduced to Herz, the director of the museum, and they fall deep into conversation about travelling and collecting. Once or twice he glances up to see Dora looking at him but both times she opens her fan and covers her face as she cools herself. The small room has become unbearably warm.

Despite his earlier reservations, the party has proved exceptionally fruitful for him. Herz will arrange for him to travel across the South Island with a man named Schlau, a fellow German currently employed by the museum to mount its considerable collection of animals and native birds. Henry is now gripped by the excitement of the adventures before him; all of the birdlife he has never seen.

He feels something akin to bloodlust, a watering in his mouth.

He forgets about Dora until he bumps into her on the stairs as he ascends to his room. She is coming the other way and presses herself against the wall, as though in fright — so different from the confident young lady he met earlier.

Goodnight, he says to her softly, but she only nods at him, keeping her eyes on him as he passes.

The next morning he finds a letter from Mr Collins. The family has been called away to their country estate. He is to make himself at home and to feel free to visit them there. He only needs to send word and a coach will come for him. He tries to remember if he has behaved badly; if he had one too many drinks at the party and said the wrong thing. But he can think of nothing out of order. Perhaps the family really does have to attend to an urgent matter. And now he is freed from politeness and can explore the country at will.

I woke in a panic. A noise had travelled through my dreams, a musical note, floating up from the front paddock, plucked again and again, a sound I had heard in my head many times since I had awoken to it all those years ago. As I lay there, my ears strained to find it, but it had dissipated. Just my imagination haunting me as usual then, not a ghost.

The curtains were still open and the night was clear. A shuffle outside, a moan. Just country noises, I told myself. The house was like a breathing body; it had always creaked and complained. But I had never been alone then. There was always someone else to investigate the sounds if they became unfriendly. I got up and crossed the room to the window. The night was still and the moon was out. Its light fell on everything outside: the neglected vegetable patch, the treehouse. Far off, through the trees, the river. It was as if the house were watching, waiting for something to move, as I was. I heard a sound, like a footstep on the gravel driveway, but only one. I pressed my face closer to the glass to peer to the left, but I would have had to climb out the window to get a look.

Magpie Hall

Magpie Hall